Eberhard Steneberg, an emigré-artist in Frankfurt.

A neglected story in the 1950s

by Dr. Inge Wierda (art historian)

Forschend übersieht dein Blick

Eine großgemeßne Weite!

Hebe mich an deine Seite

Gib der Schwärmerei dies Glück!

Und in wollustvoller Ruh,

Sah der weitverschlagne Ritter

Durch das gläserne Gegitter,

Seines Mädgens Nachten zu.

– Excerpt from the poem An den Mond

by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1)

During the museum night on 23 April 2016, a large group of people attended the guided tour of Dr. Michael Fleiter through the exhibition Schauplätze: Frankfurt in den 50er Jahren at the Institut für Stadtgeschichte in Frankfurt am Main. The audience listened attentively to the fraught history of their city. This now-booming metropolis was one of the most severely devastated cities at the end of the Second World War. Fifty-two percent of the city had been swept away by continuous English and American bombardments. A huge number of civilians (5500) lost their lives; a majority had already left the city and 45 percent of the houses disappeared. The ‘Altstadt’ (medieval town) and exquisite early-19th century Empire houses were almost completely destroyed. A few along the banks of the Main still stood and only one medieval so-called Fachwerkhaus, Haus Wertheim, survived. For decades Frankfurt am Main was a construction site with large gaps. Today, due to expansion, the city is once again a construction site with cranes dominating the skyline.

The Frankfurt municipal government used the post-war reconstruction boom of the 1950s, as an opportunity to fulfil its long-standing aspiration for radical change. (2) Despite the protests of local inhabitants, they took as their inspiration the urban model of their American occupiers, with an inner city grid filled with office buildings, banks and shops lining broad streets which afforded ample space for cars. Temporary post-war market stalls were rapidly replaced by big department stores. And in 1946, an extensive area of attractive green parkland to the south was lost in the expansion of the Rhein-Main airport, utilised by the American military. Frankfurt am Main adopted the Buchmesse from East Germany (Leipzig) in 1948 and made it flourish. (3) The city adopted the five points of architecture of the French-Swiss architect, Le Corbusier, and became a paradise for modern architecture and architects.

In the 1960s, Nordweststadt was added to the city and between the 1970s and 1990s, skyscrapers modelled after American buildings, completed the facelift of the city. Full speed and focused, Frankfurt am Main had risen out of its ashes to become the metropole; the Mainhattan of today, ruled by a consumerist and materialist lifestyle imported by its capitalist occupier. Currently known as the financial heart of Europe, it has also become a thriving artistic centre today.

During the tour of the Institut für Stadtgeschichte (in the Karmeliterkloster), I felt one significant story of Frankfurt am Main in the 1950s, had not been told. It is an account of a Russian art event during the Adenauer Era, that actually took place within its own ranks. In retrospect, at the time of Germany’s division into two states, with the influence of American culture and anti-Russian politics in Frankfurt am Main and across Europe, this story is remarkable. It is a memorable cultural intervention in Cold War politics that occurred on the initiative of one of Frankfurt’s citizens in 1959. He was Eberhard Steneberg, an artist and author, who reintroduced Russian modernism to the Modern Age.

Whilst the Americanisation of Frankfurt’s art world was established with the Amerika House in Frankfurt in May 1946, and, at the same time, with the Soviet regime sidelining this period of art history, Steneberg organised a show of modern Russian art in the Karmeliterkloster, ‘to correct the history of the Modern Age’, as he aptly described it. (3) He drew attention to the contribution of the Russian avant-garde to the Modern Age and entitled the show Beitrag der Russen zur Modernen Kunst. The exhibition in the Karmeliterkloster in 1959, was accompanied by a catalogue, remarkable in its own right, produced by Steneberg. Looking at the book in the Städel Museum Library, - a jewel in its kind -. Steneberg had invited Russian avant-gardists in exile to relate their views in one sentence. In just a few pages, Steneberg had gone to the core of the matter.

During the opening, the Oberbürgemeister and other city officials were conspicuously absent, afraid of political reprisals from the Russians. Steneberg was accused of being a communist; Bertolt Brecht’s company was still not welcome, “thus was the atmosphere at the time”, Frau Hanna Lambrette, an acquaintance of Steneberg, explained to me in an interview. They were unable to appreciate that Steneberg’s Russian avant-garde show was the first post-war exhibition in its kind since 1923. However, it set an example in the West and was quickly followed by many such shows, continuing to this day, on the topic.

In 2016; twenty years after Steneberg’s death, and within the context of the exhibition Schauplätze: Frankfurt in den 50er Jahren, it is time to tell the story and introduce the man behind it. What actually happened? Who was Steneberg?

An immigrant’s view

In 1951, Eberhard Steneberg, arrived in Frankfurt am Main with his family as immigrants from the east. Haunted by the political shifts under Adenauer in Germany and the closed atmosphere in post-war Weimar in particular, he had left his home town in 1947, met his wife shortly thereafter, and decided to pursue his ambitions as an artist in Frankfurt am Main. The Stenebergs were attracted by its liberal atmosphere; its concern for democracy and freedom. Despite good intentions, post-war Frankfurt was unable to provide the many Heimkehrer and East-German immigrants accommodation. The federal state of Hesse alone counted 750,000 homeless people. Steneberg constructed a house for himself and his family, living and working in a cramped space in Sachsenhausen for fifteen years. Like Vincent van Gogh, the Dutch artist he admired, the material circumstances were harsh and he and his family were poor, but he continued to create his art.

Let us examine three abstract paintings he made in Frankfurt in the 1950s.

Blick in die Stadt

Prior to coming to Frankfurt, Steneberg had found his way to abstraction. According to the artist, there had been no single moment of inspiration to arrive at this point. He had seen Bauhaus exhibitions and had met Lyonel Feininger in the period of the Entartete Kunst, but until 1950, he had worked in a figurative style. For Steneberg, post-war encounters with Fritz Henning had been decisive in changing his style. Henning understood Steneberg's frame of mind, and inspired him to shift his horizon from the phenomenal world to that which inspires it. Since abstract art frees an artist of political, religious, ideological and societal connotations and their judgements that go alongside these, the transformative process from figurative to abstract art had been liberating to Steneberg. It offered him a pocket of space in a world ripped apart by conflicts. It simultaneously connected him to the flourishing early modern art scenes which were curtailed by fascist regimes in Germany and Russia, just as his own artistic development had been complicated between 1933 and 1945. He belonged to the so-called verschollene Generation and was forced to live a life of commuting from one place to another in pursuit of artistic education in the 1930s, whilst simultaneously trying to avoid military service. After the war he moved among the second generation of modern artists. Moreover, as a curious intellectual, he took it upon himself to research and reintroduce the art of the first generation of modernists in Germany, Russia and France. He felt they should be made known to the younger generation in post-war Germany and given a voice.

Steneberg’s impressions of his new home found expression in Blick in die Stadt (1953, see above). In this early abstract artwork of considerable proportions, there are still several literal references to a traditional Stadtlandschaft, as well as Steneberg’s cultural background. The city in this oil painting consists of an agglomerate of small colour panes set against a dark olive background of larger ochre, green, brown colour panes. The curved shape of the upper green part resembles the shape of the Taunus; the mountain range that surrounds the city, giving it its magical flavour. The lower part has the brownish colour of Mother earth.

The centre of town is marked by black lines forming a rectangle. Behind it, a fiery orange area seems to indicate the heart of the city. It glows like fire, - perhaps reminiscent of the bombardments- and simultaneously resembles a beating heart. Although Frankfurt am Main was severely damaged, life went on. The spirit of Frankfurt’s inhabitants seemed unbroken. They focused on the city's reconstruction and collectively created what became known as the Wirtschaftwunder. The image of small pale sun or moon in the upper area of Blick in die Stadt, looks like an eye focussed on the city. It gives Steneberg’s ’view of the city’ its mysterious allure. It seems to observe the city from a bird’s eye perspective and reminds me of the poem, An den Mond, by Steneberg’s favourite author Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, as well as the Kosmische Landschaften (1917-19) by Paul Klee. (4) Steneberg knew both men from his youth. In his birthplace, Weimar, Klee taught at the Bauhaus and Goethe spent the last years of his life. It must have given the East German immigrant a joyous coming-home-feeling that a Goethehaus existed in Frankfurt am Main as in Weimar, and was restored just after his arrival in 1951. The sun/moon motif is one that we find throughout the oeuvre of these three gifted Weimar residents. Goethe had set the tone with his observations, drawings and poems of the moon.

Left: Rotunde, 1958

Right: Rotunde/Funkhaus am Dornbusch, Frankfurt am Main, 2016

Rotunde

Eberhard Steneberg was well versed in the socio-political and cultural events of his new domicile. Five years after Blick in die Stadt, he painted another large oil painting with a Frankfurter annotation, entitled 'Rotunde'. Different in style, it refers to one of the most significant post-war Schauplätzen in Frankfurt, the newly-constructed Rotunde by the architect Gerhard Weber in the Bertramstrasse 8. It is now part of the Hessische Rundfunk, but in 1948, the Rotunde was commissioned by the city as an extension to an existing building (a Pedagogical Academy) with the intention of housing the parliament of the newly-formed Bundesrepublik Deutschland in the building. However, on 10 November 1949, it was decided that the seat of the government would not go to Frankfurt am Main where German democracy originated in 1848, but to the more provincial city of Bonn. (5) This decision went hand in hand with the political and religious preferences of the politicians in power at the time: SPD-Protestant versus CDU-Catholic (Konrad Adenauer).

The difference with Blick in die Stadt is striking. Steneberg had moved from a more sombre ‘cubist’ palette to the bright palette of orphism. Yet, why did he opt for a different style? An article written by Steneberg about the founder of orphism, Robert Delaunay, provides some clues. (6) Steneberg looked upon Delaunay as one of the most significant fathers of modern abstract art. Fascinated by Delaunay’s description of orphism as ‘un langage lumineux (cortège d’Orphée)’, he explains that art is orpheic, powerful as the music of Orpheus, and in that sense stands above science. He further explains that art is ‘orphistic’ or mystical, due to its capacity to reveal the essence of nature. Where scientists use the physical eyes to analyse the secrets of nature, Steneberg states by Goethe and Caus, that ‘geistige Augen’ intuitively process impressions and reproduce the essence of the whole in an artistic fashion. In short, orphists are interested in the essence of nature, its non-fysical, mystical and eternal dimension. In Rotunde, Steneberg - in the same vein as Delaunay - constructed with colour. No colour exists in isolation, each should be perceived simultaneously: in contrast with, in interdependence with and in unison with other colours. Together they perform the dynamic and colourful dance of life.

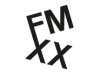

Left: Paulskirche, Frankfurt am Main

Middle: Rotunde, 1948 / Funkhaus, since 1951

Right: R. Delaunay, Sun and moon simultaneously, 1913

In Steneberg’s Rotunde, circular colour planes recur at several places on the canvas. Frankfurt Stadt had also chosen the perfect form of a circle as its basic plan for buildings of historical significance: an attempt to unite the nation on democratic ideals. The Rotunde, commissioned in 1948, is reminiscent of the central building plan of the Paulskirche. It was in this ‘church’ that the first attempt to construct a democratic society had taken place a century earlier. It was also the first building to be reconstructed after the devastation of the war. A new beginning was to be made. “Nie wieder Krieg”, shouted youngsters at a protest march in Frankfurt in 1957: “Frankfurt Stadt für Alle”, inhabitants are shouting in 2016.

From 1951, the Rotunde became the pride of the Frankfurter Funkhaus am Dornbusch. It united people, not politically, but around orphic events: concerts, lectures, etc. Naturally, its Rohbau predates the 1950s and a photograph is therefore missing in the current exhibition in the Institut für Stadtgeschichte. But Steneberg brought it to the fore, as a symbol in the late 1940s and 1950s in Frankfurt am Main, intended to unite around democratic ideals and cultural events.

Ohne Titel, 1959

1959

In the third and last oil painting, we can see that in 1959, the year of the Russian show, Steneberg once again made a shift in style. We recognise modern red, black and blue, geometric forms and a neutral background from well-known art works of Russian modernists such as Kazimir Malevich. Although Steneberg was highly fascinated by their work, he refrained from cold abstraction in his own oeuvre. He remained a craftsman, using a brush and oil paint, closer to early German modernism (Bauhaus), than to strict geometric abstract art of Russian constructivists and productivists, Dutch De Stijl artists or the Hungarian Bauhäusler Maholy-Nagy, who he nevertheless admired. By contrast to this first generation of modernists, Steneberg dedicated himself entirely to painting and discarded the utilitarian function of art. He avoided the use of technical drawing instruments such as a compass, ruler and geometry set squares. Close to Malevich, Eberhard Steneberg critically reflected and published on art and life, was a magician with colours and a 20th century modern artist. He enjoyed the company of Russian émigré artists in Paris, some who had achieved some fame: Natalya Goncharova, Mikhail Larionov, Sonia Delaunay, Pavel Mansurov etc.

Steneberg died in 1996 in Frankfurt am Main neither a communist, a constructivist, a capitalist or a consumerist. He had not aligned himself to any group, but was a 20th century modernist painter pur sang. In many ways his generation of artists had lived through difficult political, socio-economic and cultural circumstances, but with a nod to Goethe and Klee, the sun and moon reminded him of our amazing existence in a vast cosmos. In 1993, when the majority of the world pursued the dominant American lifestyle and saw the “plattester Marktradikalismus als Heilsbringer religion”, Steneberg paid tribute to the sun and moon as Goethe, Klee, and Delaunay had done before him, and hopefully many more will do in the future. (7)

Postscript

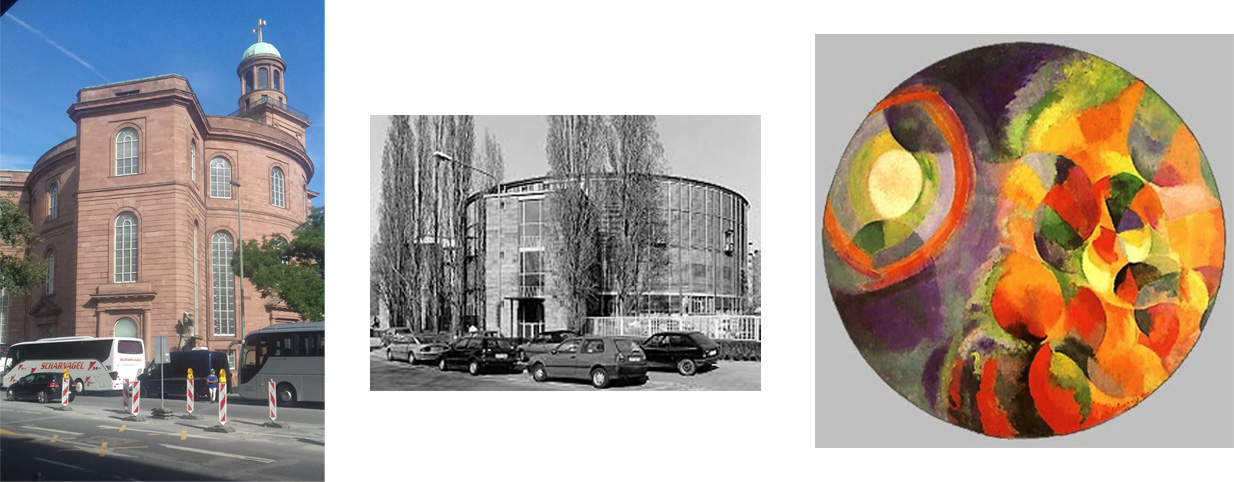

Meanwhile, Russian modernism is embraced in the logo of the Frankfurter Messe.

Steneberg created the prelude for this embrace in the 1950s.

Links: Logo Frankfurter Messe

Mitte: View on Frankfurt am Main, 2016

Rechts: Steneberg, Sonne und Mond, 1993

Notes

(1) Mathias Mayer, Goethes Monde (Berlin: Insel Verlag, 2012), pp. 6-8, 8.

(2) Schauplatze: Frankfurt in den 50er Jahren, ex.cat. Frankfurt am Main: Institut für Stadtgeschichte. Karmeliter Kloster, p. 6.

(3) Ibid, p. 165.

(4) In the late 1930s, many European artists sought refuge in the Unted States, helping to bring about a second revolutionary moment in the Modernist Age: a shift from the former artistic centre in Germany to the US, particularly New York.

(5) Paul Klee. 50 Werke aus 50 Jahren, ex.cat., Hamburg, Hamburger Kunsthalle, 1990, S. 81.

(6) For more information on the choice of Bonn, see: Vor 40 Jahren: Bonn oder Frankfurt. Der Streit um die Bundeshauptstadt. Dokumente, Photographien und Karikaturen aus dem Besitz des Stadtarchivs der Stadt Frankfurt am Main, ex.cat. 16 Jan-31 Marz 1989, Kleine Schriften des Frankfurter Stadtarchivs 2 (Ausstellung und Beiheft: Ingrid Röschlau); See also photos of the original Rotunde in: Heinz Schomann, Volker Rödel, Heike Kaiser, Denkmaltopographie (FFM: Societäts-Verlag, 1994 (2. Auflage), 1ste uitg. 1986)

(7) Eberhard Steneberg, ‘Robert Delaunay und die deutsche Malerei’, Das Kunstwerk, vol. 15, no. 4, 1961, 22-23.

(8) Thomas Wieczorek, Die verblödete Republik. Wie uns Medien, Wirtschaft und Politik für dumm verkaufen (Munich: Knaur, 2009), p. 24.